- Home

- Angry by Choice

- Catalogue of Organisms

- Chinleana

- Doc Madhattan

- Games with Words

- Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

- History of Geology

- Moss Plants and More

- Pleiotropy

- Plektix

- RRResearch

- Skeptic Wonder

- The Culture of Chemistry

- The Curious Wavefunction

- The Phytophactor

- The View from a Microbiologist

- Variety of Life

Field of Science

-

-

Change of address6 months ago in Variety of Life

-

Change of address6 months ago in Catalogue of Organisms

-

-

Earth Day: Pogo and our responsibility9 months ago in Doc Madhattan

-

What I Read 202410 months ago in Angry by Choice

-

I've moved to Substack. Come join me there.11 months ago in Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

-

-

-

-

Histological Evidence of Trauma in Dicynodont Tusks7 years ago in Chinleana

-

Posted: July 21, 2018 at 03:03PM7 years ago in Field Notes

-

Why doesn't all the GTA get taken up?7 years ago in RRResearch

-

-

Harnessing innate immunity to cure HIV9 years ago in Rule of 6ix

-

-

-

-

-

-

post doc job opportunity on ribosome biochemistry!10 years ago in Protein Evolution and Other Musings

-

Blogging Microbes- Communicating Microbiology to Netizens11 years ago in Memoirs of a Defective Brain

-

Re-Blog: June Was 6th Warmest Globally11 years ago in The View from a Microbiologist

-

-

-

The Lure of the Obscure? Guest Post by Frank Stahl13 years ago in Sex, Genes & Evolution

-

-

Lab Rat Moving House14 years ago in Life of a Lab Rat

-

Goodbye FoS, thanks for all the laughs14 years ago in Disease Prone

-

-

Slideshow of NASA's Stardust-NExT Mission Comet Tempel 1 Flyby14 years ago in The Large Picture Blog

-

in The Biology Files

A plant pundit comments on plants, the foibles and fun of academic life, and other things of interest.

Prunophobia? Don't stand too close!

The single most common gardening mistake TPP observes is poor pruning, including none pruning. Knowing how plants grow is essential, but you can learn most of what you need to know by careful observation. Knowing what you want to accomplish is also essential. Knowing that poodling (and here) is a total no-no is totally essential. So what can possibly go wrong? No wonder many people fear pruning to the point that they make an even greater mistake - they don't prune at all. Now you put pruning shears into TPP's hands and that mild-mannered, easy-going botanist turns into a clipping demon! Don't stand too close, and please, never, ever point! Snip! Oops. Sorry. Of course some plants are a struggle. Two dwarf apples of the same variety, and one is well-behaved and the other is growing all over the place. They are clones aren't they? And who would have ever thought that one of the most difficult pruning challenges is a thread-leafed (branched) Chamaecyparis? Don't prune enough and it takes over; prune too much and it won't grow back. Oh, and it grows fast too, so it's real battle. Here's the things to look for with fruit trees: multiple leaders (leave only 1), downward growing branches, criss-crossing branches, weak branches, damaged or broken branches, suckers (a problem with grafted stock), vigorous new growth (reduce by 1/2 to 1/3). If more than 2/3s of a branch needs to be removed, remove the whole thing. Cut branches perpendicularly and cleanly. Cut branches off flush to the stem; they heal faster. Don't cheap out on your equipment. Don't ever go near a tree or shrub with a chain saw unless to intend to basal prune it. One real problem is that you need the right size clippers for the job, and they get bigger for bigger branches, but then they can be too big for some people's hands (this from Mrs. Phactor). Good loppers are needed for big branches or major pruning, and they can provide a lot of mechanical advantage. Keep them sharp. If you find a rusty pair laying around somewhere, it may belong to yours truly. A pair went missing somewhere out there a few years back. TPP's earliest lesson on pruning came from a great gardener who told his young helper to prune out the oldest stems from some lilacs and beauty bushes. When TPP asked how much to prune, his response was "there should be room for the birds to fly". When the job was done, and being inspected, he let out a big sigh, "Ah, here I was thinking of sparrows, and you were thinking of eagles." But, nonetheless, for the next few years they looked great.

Spring garden assessment

This wasn't a particularly bad winter except the coldest weather was not accompanied by snow cover, so plants were quite exposed. Now that spring growth is beginning some assessment of winter damage can be made. Two new mountain laurels took a beating; one might survive, the other is toast. A Leptodermis also new last year looks like a loss as well. A big old Annabelle hydrangea looks like a weed whacker went after it, but it was just bunnies. Most of the trees and shrubs that we expended water on look pretty good this spring, which shows that winter cold often gets the blame for death caused by prior drought. A dwarf hemlock looks OK, and given TPP's track record with this species (0 for 3 attempts) it's a good sign for it to just be alive. Our nominee for most improved (at this point) is a flowering quince that got severely bunnied last year, but recovered very nicely from within it's cage. A Pieris has better flower buds than it has had for many years. Hoping for one or two magnolias to flower for the first time: odds on butterfly magnolia - almost certain; odds on Oyama magnolia - still a long shot. A better evaluation of the patients will be possible as the season progresses. Bright note: Iris reticulata multiplied nicely since last year (their first), and it's such a cheerfully colorful early bulb when planted in mass. Drought didn't matter much because they go dormant in the summer heat.

A fool's bet

A creationist kinesiologist named Mastropaolo is getting his 15 minutes of fame by publically challenging “evolutionists” to bet $10,000 with him that they can’t disprove

Genesis, and a hand picked superior court judge gets to decide. This is almost criminally stupid. His challenge is based on the false premise

that an either-or dichotomy exists, i.e., if not evolution, then Genesis. But if not evolution, why not Valhalla or the Dream time? Now there’s a reason that we don’t take our

scientific findings to court; judges don’t know squat about science and are no

better than anyone else at deciding what data means or why it is critical. The whole legal concept of evidence is quite

different from evidence in science.

Might as well challenge this guy to prove that the Norse gods don’t

exist, especially on next Thors’day.

Now of course the whole purpose of this exercise is so he can crow about

how no one took him up on his challenge, a result that clearly demonstrates the

vacuity of science. Alfred Russel Wallace, the British naturalist

that independently thought of the idea of natural selection, got sucked into a

similar challenge to prove that the surface of the Earth wasn’t flat. Wallace had a clever idea. He knew of a straight canal with series of

bridges in a row. He affixed a stick to

each bridge the exact same height above the level surface of the water. Then backing off one more bridge, Wallace set

up a telescope, and voila, the top of each successively further stick was slightly lower than

the previous showing that the surface of the "flat" canal was

curved by a measurable amount.

Independent witnesses concluded that Wallace had demonstrated that the

surface of the Earth was not flat, but the challenger claimed he could see

nothing in the telescope and wouldn’t pay up.

And similar blind justice is just what our kinesiologist wants as well; nothing you can say or

demonstrate scientifically will disprove anything about Genesis. And who cares? The bet is just setting up a straw man so it can be

knocked down. Science has pretty high

standards of evidence, and you don’t get to ignore any of it. If you don’t like an explanation, you must

propose a different one that accounts for everything. This is too tough a game for Mastropaolo, so

he wants a different playing field, one that isn’t used in science because

rigging the game is the only way he will play, and this tells you all you

need to know about him.

Spring flowering - 2012 & 2013

Spring 2012 was quite bizarre, and while spring 2013 is decidedly late, it's closer to the norm than was 2012. Yesterday's post snow storm warming resulted in late crocus, aconite, and Iris reticulata popping into bloom as well as the culmination of a very long prelude of hybrid hellebores. This brings the total number of flowering events for our estate to 8 as of March 28th. Last year the unseasonably warm weather pushed spring flowering along so fast that 92 flowering events had taken place by the same date! That like 1/3 of everything in our gardens, before April 1st! 2012 was totally out of whack. In 2010 and 2011 the number of flowering events by 3/28 was 10 and 11 (aconite was new in 2011 accounting for the difference). Lots of plants are just waiting for a bit of real spring weather: American filbert, numerous bulbs, Abeliophyllum, Cornus mas, Forsythia, Helleborus niger. And of course the early spring garden work is behind schedule too, but the cold frame crops will be planted this weekend, which is just about normal (~April 1th) for around here. This also means that the beginning of field season is just around the corner too. Hope someone burns TPP's prairie!

Pollen is not plant sperm

Anything plant related, no matter how crazy, gets directed to TPP. So it was that TPP finds himself being interviewed about seasonal allergies. Right? Actually having talked to a bunch of allergists, the writer found themselves wondering about pollen, so she gets sent to someone who knows a little bit about how pollen works from the floral perspective. OK, so I know pollen is plant sperm, but why does it irritate your nose? First, pollen is not plant sperm, it's a whole, albeit microscopically small, male organism, and like all males, it produces sperm after pollination takes place. What? It's a male? Then where is the female? Hmm, this lady is quicker than most of my students who never think to ask that question. She's there, residing inside each and every ovule, which is not an egg, housed within an ovary, which is not a sex organ. Those traditional names are a testament to the same misconception about plant sex that you started with. Pollen isn't sperm; and a plant ovule isn't an egg. TPP wonders how many times he's explained this during his career and seemingly with no impact what so ever except perhaps on a case by case basis. Misconceptions about plants have more lives, and much longer lives, than a cat. The true nature of the seed plant life cycle has been understood since Wilhelm Hofmeister published his magnum opus on plant evolution in 1851. So that's only been a mere 162 years, and still a jacketed megasporangium is called an ovule (although TPP does admit the convenience of the term, which botanists still use while knowing it implies pure wrong thinking). However, at the end of my lesson, my interviewer said, "Oh, you're good! You explain things so well." Thank you, and it only took 43 years of practice.

A tiny bit less colorful

This morning was really quite lovely with a promise, a true promise, of spring in the air, but perhaps just a tad less colorful than it was. By strange coincidence, on the way to my coffee shoppe, TPP glanced in the window of a used record store and front and center was a toy Yellow Submarine; how very nostalgic, and this was before discovering that Jack Stokes had died draining just a little bit of color out of the world. He was best known for being the animation director of the Yellow Submarine. In 1968 the Yellow Submarine was the epitome of creativity, a story that somehow managed to link a bunch of unrelated Beatles' songs together in a fanciful manner. The whole animated film was just so imaginative. TPP thinks his F1 still has a Blue Meanie squeeze toy (Max maybe?). Clearly the music and the film left an impression on himself.

This morning was really quite lovely with a promise, a true promise, of spring in the air, but perhaps just a tad less colorful than it was. By strange coincidence, on the way to my coffee shoppe, TPP glanced in the window of a used record store and front and center was a toy Yellow Submarine; how very nostalgic, and this was before discovering that Jack Stokes had died draining just a little bit of color out of the world. He was best known for being the animation director of the Yellow Submarine. In 1968 the Yellow Submarine was the epitome of creativity, a story that somehow managed to link a bunch of unrelated Beatles' songs together in a fanciful manner. The whole animated film was just so imaginative. TPP thinks his F1 still has a Blue Meanie squeeze toy (Max maybe?). Clearly the music and the film left an impression on himself.

Who took the preserved ginkgo?

Specimens are always a problem, and how can you teach students about organisms if you can't put the organism, or at least significant pieces thereof, into their hot little hands? Let's say you want your students to understand the reproductive structures of a ginkgo, using them to compare to those of conifers, so you have to have specimens. Now with this in mind, TPP had collected pollen cones and ovulate structures from ginkgo trees and preserved them in ethanol, two half gallon jars of pickled ginkgo, enough to last for years. The other reason this is necessary is that ginkgo trees don't produce these structures except once a year, usually in the last week of the semester on average, and the lab class is always at a different time of year. So you go to the cupboard, and there's only one jar; it says ovulate ginkgo on the lid's label, but it's actually pollen cones. Where the bloody hell is the other jar? Someone used them, and accidentally switched the lids, but for reasons as yet undetermined, did not replace the other jar. The problem with this is that by the time you figure this out, it's too late. Even if this had been know at the beginning of the semester, it makes no difference because you can't just go out and buy pickled reproductive structures of ginkgo. They're only good for just one thing, teaching, and nobody who teaches knows anything. Something is very suspicious, very suspicious indeed. There are only so many classes that would use such specimens, and only certain people instruct those classes, so the number of suspects is pretty finite. Some wandering gypsies didn't make off with them and no ransom notes have been received. Ginkgo? Oh, yeah, them trees. Seems my colleagues have pretty good alibis or very convenient memories. Guess some things should be kept under lock and key, but TPP is just so trusting. Now to remember that new specimens are needed when the ginkgo pollination season rolls around again.

Specimens are always a problem, and how can you teach students about organisms if you can't put the organism, or at least significant pieces thereof, into their hot little hands? Let's say you want your students to understand the reproductive structures of a ginkgo, using them to compare to those of conifers, so you have to have specimens. Now with this in mind, TPP had collected pollen cones and ovulate structures from ginkgo trees and preserved them in ethanol, two half gallon jars of pickled ginkgo, enough to last for years. The other reason this is necessary is that ginkgo trees don't produce these structures except once a year, usually in the last week of the semester on average, and the lab class is always at a different time of year. So you go to the cupboard, and there's only one jar; it says ovulate ginkgo on the lid's label, but it's actually pollen cones. Where the bloody hell is the other jar? Someone used them, and accidentally switched the lids, but for reasons as yet undetermined, did not replace the other jar. The problem with this is that by the time you figure this out, it's too late. Even if this had been know at the beginning of the semester, it makes no difference because you can't just go out and buy pickled reproductive structures of ginkgo. They're only good for just one thing, teaching, and nobody who teaches knows anything. Something is very suspicious, very suspicious indeed. There are only so many classes that would use such specimens, and only certain people instruct those classes, so the number of suspects is pretty finite. Some wandering gypsies didn't make off with them and no ransom notes have been received. Ginkgo? Oh, yeah, them trees. Seems my colleagues have pretty good alibis or very convenient memories. Guess some things should be kept under lock and key, but TPP is just so trusting. Now to remember that new specimens are needed when the ginkgo pollination season rolls around again.

Today's lab - Cycads

Cycads are one of TPP's favorite groups of organisms. Cycads are the dinosaurs of the plant kingdom, the oldest living lineage of seed plants with a history stretching back to the late Permian, real living denizens of Jurassic Park. Most people think cycads are palms and some common names (sago palm) suggest as much, but cycads are really, really different. Generally cycads are more similar to ferns. They have fronds that develop from fiddle heads and they have their sporangia on modified leaves. Among gymnosperms, cycads are the only organisms that are predominately insect pollinated. Our glasshouse has 8 of the 11 genera, so that will keep my students busy for awhile looking for cones, fiddle heads, coralloid roots, and all the rest. The specimen shown is a species of the southern African Encephalartos bearing seed cones.

Snow day - Student interpretation

University campuses are a great place to work, to spend your time, because there's always something going one: mad things, crazy things, zany things, serious things, nothings, etc. Yesterday was a snow day, so do not come to campus unless you are essential personnel. Well, students are certainly essential to a university, so what does having a snow day mean to students? Their obvious interpretation is that a snow day is for playing in the snow. Since the primary reason for a snow day is the convenience of commuters, the campus residents are there ready to go, and nature supplied a goodly amount of nice mouldable snow and the accompanying temperatures were quite mild, it was perfect day for snow play. The main quad of our campus now sports about two to three dozen snow "sculptures", which they must be called since the size and creativity goes far beyond mere snow men, and in several cases the gender was not at all left in question. A couple of strategically placed snow forts suggested a battle, or at least ambushes of anyone so foolish as to be walking on the sidewalk between them. In one case a tree had a new suit of clothes around its trunk, but white is wrong for the season. Perhaps coming to a Youtube near you, an avant-garde film of a young Asian woman in a pink bikini and naught else cavorting in the snow while being pelted with snow balls. Otherwise, who knows? So, yes, students certainly know what to do on a snow day. TPP worked on illustrations for a publication. Yes, very lame.

Speaking of snow - and soccer - and Costa Rica

TTP has spent a lot of time in Costa Rica doing research and teaching, and every now and then just being a gringo tourista. Snow days here in the upper midwest are no big deal really. But some things, just like dogs and cats together, are just unnatural. So when TPP saw this soccer game the other day, it was just plain wrong, a crime against nature. Soccer is one of those games that is played under diverse field conditions, but this was not right. Cold, OK. Some flurries in the air, OK. But when the ball can't roll because of snow accumulation, this just isn't right. You can't play the game the way it was meant to be played. And then there's the whole Costa Rican thing. They love soccer way more than the USA loves soccer. It's their love and their pride at stake. So you take the Costa Rican national team and you ask them to play soccer in a form of precipitation that they have never, ever seen before, a form of precipitation that most Costa Ricans can't even imagine, and it's just plain wrong. Most of them probably cannot believe even still that they were playing soccer under such conditions, and then to lose late, by one goal; outrageous! Never has the weather conditions been so stacked against one team before. Their protest is most appropriate, and hopefully it will be upheld.

TTP has spent a lot of time in Costa Rica doing research and teaching, and every now and then just being a gringo tourista. Snow days here in the upper midwest are no big deal really. But some things, just like dogs and cats together, are just unnatural. So when TPP saw this soccer game the other day, it was just plain wrong, a crime against nature. Soccer is one of those games that is played under diverse field conditions, but this was not right. Cold, OK. Some flurries in the air, OK. But when the ball can't roll because of snow accumulation, this just isn't right. You can't play the game the way it was meant to be played. And then there's the whole Costa Rican thing. They love soccer way more than the USA loves soccer. It's their love and their pride at stake. So you take the Costa Rican national team and you ask them to play soccer in a form of precipitation that they have never, ever seen before, a form of precipitation that most Costa Ricans can't even imagine, and it's just plain wrong. Most of them probably cannot believe even still that they were playing soccer under such conditions, and then to lose late, by one goal; outrageous! Never has the weather conditions been so stacked against one team before. Their protest is most appropriate, and hopefully it will be upheld.

Snow Day

Snow day! Whoda thunk it? It's been so long since our university had a snow day TPP can't remember the last. The usual reason for the snow day is the time it takes to clear parking lots, or a lot of wind makes driving outside of town dangerous. Us pedestrian (or X-country ski) commuters present no problem although the cheap skate land lords whose buildings ring the campus for a couple of blocks in all directions never clear their sidewalks, the simple obligation of all property owners. TPP had an exam scheduled today, so my students will feel like they got a reprieve.

It's actually a beautiful scene this morning because this was a heavy snow that has stuck to all the trees and shrubs hopefully without damaging them. Some 7-8 inches of snow is nothing for us natives of the New York State snow belt, but for here this is a lot of snow. The cardinals certainly stand out boldly, and when foraging is difficult, large numbers of birds and squirrels gather at our feeding stations, and the rest of the food chain lurks. The kitty-girls just watch the activity out of our kitchen windows. The massive red-tailed hawk is perched in a tree over the garage and about 80 feet beyond a Cooper's hawk is perched waiting for its chance. But it's time to get moving, and we've got a big, long sidewalk to clear, but not too many people are out and about.

It's actually a beautiful scene this morning because this was a heavy snow that has stuck to all the trees and shrubs hopefully without damaging them. Some 7-8 inches of snow is nothing for us natives of the New York State snow belt, but for here this is a lot of snow. The cardinals certainly stand out boldly, and when foraging is difficult, large numbers of birds and squirrels gather at our feeding stations, and the rest of the food chain lurks. The kitty-girls just watch the activity out of our kitchen windows. The massive red-tailed hawk is perched in a tree over the garage and about 80 feet beyond a Cooper's hawk is perched waiting for its chance. But it's time to get moving, and we've got a big, long sidewalk to clear, but not too many people are out and about.

Pre-season training

Today, a Saturday, is a typical enough late March day, just a bit cool, but OK to do some pruning; still too cold to actually plant anything. The forecast for tomorrow is a winter storm that could bring several inches of heavy wet snow. Great. However, some things still need to be done, some pre-season preparation. TPP must go out and buy several cubic feet of potting mix because it will be used to plant early season flowers, e.g., pansies, and cold frame crops: lettuce, spinach, baby bok choi, green onions. And to be ready for this some seed shopping is in order, except none of our local garden shops ever carry baby bok choi seeds, so some will have to be mail ordered. Even if you only have a small space, even if you only do a little gardening, a cold frame is a great low tech investment. You can easily extend your gardening season by 2 months and even keep your parsley happy well into winter. TPP likes the smaller, portable cold frames that can be used in different places at different times. Generally my cold frame crops get planted in planter boxes rather than in the soil below. The boxes are also portable and they warm up faster than the soil below. Next will come some gardener exercise, in this case, all the deep knee bends and back bends needed to clip off all of the dead perennials. Unfortunately this is exactly what TPP does for his early field work, and his back is just not getting any younger. While students can often be conned into helping with the field work, it probably isn't ethical to con them into helping with his gardens. Sadly there are still a lot of leaves left to clean up, mostly those lodged in the various garden beds. All of this will be rendered moot for at least another week by the arrival of snow.

Nature coming into balance

Small mammals sometimes have their highest populations in urban areas; human habitations provide food and shelter, and few of their predators do well in urban areas. So it was with this in mind that the Phactors cheered the arrival of a pair of red-tailed hawks in the vicinity of our little part of urban nature. Having been alerted to their presence, although they are bloody hard to miss, neighbors report seeing on one occasion a hawk dining on fox squirrel and from another direction, a bit of fresh rabbit. For the time being these top predators, not usually urban dwellers, seem to be doing quite well for themselves, and in the process tipping nature back into balance. This is just great! The bunnies in particular are out of control and one of the ways you can tell is when they nibble on things that they usually leave completely alone: scilla, crocus, and the ever-green leaves of a rock garden pink. On campus a wide array of shrubs have been quite thoroughly girdled where bunnies have gnawed the bark off. The Phactors set up an elaborate gulag of fenced concentration camps through out the yard to keep the bunnies at bay. Now of course if a great blue heron shows up in the lily pond, we'll be singing a different tune.

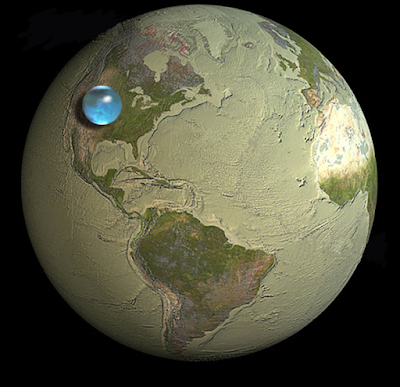

Water, water, everywhere - NOT!

As part of a regular exercise to make biology students think a bit about bigger pictures, public concerns, TPP asks them to identify and try to decide about an increasingly scarce resource. They do a commendable job, their list covers most of the usual suspects, but it seldom, if ever (memory fails me) mentions water. For the most part people don't realize how much water you use directly every day; almost nobody realizes how much water their life-style uses especially to provide your food, your clothing, even your morning newspaper (which even if it is calculated doesn't include the water needed to grow the tree to provide the paper pulp). TPP's biggest concern about fracking here in Lincolnland is how much water the process uses and no one will tell you where all this water is going to come from. Today is World Water Day. A lot of people have become aware of their carbon-footprint, but how many people know their water footprint? As the drought continues (no it isn't over) here in the midwestern USA, people are discovering that having enough water can be a challenge. But here's an image from last year's Discover Magazine to put water in perspective. It's a picture of the Earth with all of the water from all the oceans and lakes formed into a single sphere and there it is. All of Earth's water. Shows you how shallow your knowledge of water really is. Granted that's still a big sphere, but only 4% of that sphere is fresh water. Water is an increasingly scarce resource. Be responsible. 1st thing to go; water hungry, perpetually green grass lawns, a complete and total waste of water.

As part of a regular exercise to make biology students think a bit about bigger pictures, public concerns, TPP asks them to identify and try to decide about an increasingly scarce resource. They do a commendable job, their list covers most of the usual suspects, but it seldom, if ever (memory fails me) mentions water. For the most part people don't realize how much water you use directly every day; almost nobody realizes how much water their life-style uses especially to provide your food, your clothing, even your morning newspaper (which even if it is calculated doesn't include the water needed to grow the tree to provide the paper pulp). TPP's biggest concern about fracking here in Lincolnland is how much water the process uses and no one will tell you where all this water is going to come from. Today is World Water Day. A lot of people have become aware of their carbon-footprint, but how many people know their water footprint? As the drought continues (no it isn't over) here in the midwestern USA, people are discovering that having enough water can be a challenge. But here's an image from last year's Discover Magazine to put water in perspective. It's a picture of the Earth with all of the water from all the oceans and lakes formed into a single sphere and there it is. All of Earth's water. Shows you how shallow your knowledge of water really is. Granted that's still a big sphere, but only 4% of that sphere is fresh water. Water is an increasingly scarce resource. Be responsible. 1st thing to go; water hungry, perpetually green grass lawns, a complete and total waste of water.

Obama scores a point

TPP isn't a huge fan of our president, e.g. drones, habeas corpus, secrecy ,and more, but he's certain that Mittens and Eddie Munster would have been a great deal worse. So given much of TPP's disappointment, he was extraordinarily pleased that Obama presented the government of Israel with a magnolia, Magnolia grandiflora, it appears, the southern magnolia. Now this is a world-class gift! One that TPP is quite jealous of. Imagine my surprise when last year a quite remarkable local private garden sported a very hardy southern magnolia. It's just no fair! TPP's garden doesn't have a location that protected, so he must make do with other magnolias. In an effort to be modest, TPP will not intimate that the idea of giving a magnolia, instead of the ever so trite Franklinia, was his.

First day of spring - hardly!

The calendar is telling us today is the first day of spring; the weather is not. It was blustery and in the low 20s (-6 C) this morning, and the walk to the coffee shop and then to campus just about froze my arse off. Such is the particular magic of wind chill. Walking into a warm and moist coffee shop on such a day and your glasses totally fog, so happy spring to all the unidentified regular patrons who greeted TPP this morning. Tonight the low temperature is supposed to be 13 F (-10.6 C), diametrically the opposite of last year, and quite a few people asked, "Will this hurt our plants?" Possibly, but not fatally. As late winter advances, buds swell and bulbs send up leaves and buds, and they progressively become less cold hardy. This varies greatly with the state of plant growth and the temperature. If peach blossoms were showing pink in such temperatures, they're toast. If your hellebore blossoms are showing pink, it's no worry. Even so, the peach tree is hardy and will survive because flower buds as the approach flowering are among the most tender parts of the plant. Of course the point in having some plants is to have them flower and fruit, but some years the weather gods get you. Still TPP would rather not have temperatures get so low this time of year, and we may hope that this is the last of the really cold temperatures.

Gadzooks! Another bamboo bicycle!

The intertubes are just alive with cool vehicles today! Here's a bamboo tricyle actually, but boy, are you going to get noticed arriving at the office in this baby! Love the way this trike looks! But rather than bamboo, could this be rattan? Whatever, it combines a sort of classic with a futuristic look. And it was so cool to look at that TPP almost didn't realize what he could see in the background. Any of you other world travelers recognize where this photograph was taken? Hope my F1 is observant. Yes, Melbourne, Australia.

The intertubes are just alive with cool vehicles today! Here's a bamboo tricyle actually, but boy, are you going to get noticed arriving at the office in this baby! Love the way this trike looks! But rather than bamboo, could this be rattan? Whatever, it combines a sort of classic with a futuristic look. And it was so cool to look at that TPP almost didn't realize what he could see in the background. Any of you other world travelers recognize where this photograph was taken? Hope my F1 is observant. Yes, Melbourne, Australia.

futuristic city bicycle

What a cool concept bicycle! Look at this thing! In particular the rim drive makes for spokeless wheels for such an unusual look. It's just great to see so much creativity in bicycle design. No center bar so reasonably well dressed people don't have to kick their leg up and over. This is a problem with TPP's BikeE where the chain comes just too close to your pant leg to allow you to wear anything but shorts unless you like dark grease stains.

What a cool concept bicycle! Look at this thing! In particular the rim drive makes for spokeless wheels for such an unusual look. It's just great to see so much creativity in bicycle design. No center bar so reasonably well dressed people don't have to kick their leg up and over. This is a problem with TPP's BikeE where the chain comes just too close to your pant leg to allow you to wear anything but shorts unless you like dark grease stains.

Forcing some spring

It's definitely a late spring here in the upper midwest of the USA. There isn't much you can do about it, but this may help. Try forcing some flowering shrubs into bloom. This time of year it's pretty easy to do because the buds have begun to swell and they're just waiting for a bit of warm weather. In particular shrubs like forsythia are really, really easy to force into bloom. Just prune off a few long branches that you probably needed to prune anyways, particularly if you're a terrible poodler of shrubs. Put them into a big vase and it'll take about a week at household temperatures to get the buds to open. Other shrubs might take longer, but this will help you get spring going a bit sooner.

Today's lab - water ferns

The water ferns are so-called because of their aquatic or semi-aquatic habitats. There are two families the free-floating mosquito ferns, Azolla and Salvinia, and the rhizomatous clover ferns, Marsilea, Regnellidium, and Pilularia. The two pair of pinnae (leaflets) sported by Marsilea look a bit like clover, but the venation is all wrong, so they used to use them in the manufacture of good luck charms where they were embedded in plastic as a fob in lieu of getting lucky enough to actually find a four-leafed clover. Regnellidium has just one pair of pinnae, and Pilularia has no pairs having a pinnae-less frond (a pun-loving friend used to call this the "pauper" fern). These ferns grow in shallow water their rhizome rooted along the bottom. The leafier genera have emergent leaves, while the leafless genus can grow completely submerged. Azolla is used in aqua-culture, primarily rice paddies, because it has a symbiotic interaction with the cyanobacterium Anabaena, a nitrogen-fixer. They do lots of interesting things in addition. They form seed-like fertile leaves for surviving droughts. They are the only heterosporous ferns, large spores forming female gametophytes, and small spores forming male gametophytes, modifications for rapidly getting through the haploid phase of their life cycle. And they look pretty cool although not very fern-like in the traditional sense. The image shows one node of Salvinia with a whorl of three leaves, two floating leaves, and a root-like disected submerged leaf, which is also the fertile frond (round sori are visible).

The water ferns are so-called because of their aquatic or semi-aquatic habitats. There are two families the free-floating mosquito ferns, Azolla and Salvinia, and the rhizomatous clover ferns, Marsilea, Regnellidium, and Pilularia. The two pair of pinnae (leaflets) sported by Marsilea look a bit like clover, but the venation is all wrong, so they used to use them in the manufacture of good luck charms where they were embedded in plastic as a fob in lieu of getting lucky enough to actually find a four-leafed clover. Regnellidium has just one pair of pinnae, and Pilularia has no pairs having a pinnae-less frond (a pun-loving friend used to call this the "pauper" fern). These ferns grow in shallow water their rhizome rooted along the bottom. The leafier genera have emergent leaves, while the leafless genus can grow completely submerged. Azolla is used in aqua-culture, primarily rice paddies, because it has a symbiotic interaction with the cyanobacterium Anabaena, a nitrogen-fixer. They do lots of interesting things in addition. They form seed-like fertile leaves for surviving droughts. They are the only heterosporous ferns, large spores forming female gametophytes, and small spores forming male gametophytes, modifications for rapidly getting through the haploid phase of their life cycle. And they look pretty cool although not very fern-like in the traditional sense. The image shows one node of Salvinia with a whorl of three leaves, two floating leaves, and a root-like disected submerged leaf, which is also the fertile frond (round sori are visible).

Late Spring 2013

Data is the stuff that keeps you from disremembering things wrongly. This morning Mrs. Phactor says, "It seems like a late spring." Actually, it's not so late except in comparison to the truly unusually early spring of 2012. So what does the data actually say. As of March 17th, only 3 things have flowered, and two of them just barely: witchhazel, snowdrops, and early crocus. Hellebores are showing colored buds, and a warmish day would have them open, but none are in the immediate offing. Here's the list from 2012 as of March 17th (in order): witchhazel, snowdrops, early crocus, late crocus, aconite, hellebores (hybrids), scilla, tiny crocus, American filbert, Iris reticulata, dwarf daffodils, lungwort cornelian cherry (Cornus mas), early standard daffodils, Helleborus niger, European filbert, Abeliophyllum (dwarf forsythia), creeping charlie, periwinkle, spice bush, bloodroot, forsythia, Japanese pachysandra, Korean azalea, Nanking cherry, Kaufmanii tulips, Pieris, winter hazel, spring beauty, star magnolia, rue anemone. Up to now in 2013 - 3 flowering events; last year at the same time 31 flowering events. So yes, 2013 seems pretty late, but if you go back to 2011 and 2010, then 2013 doesn't seem quite so late. As of now 6 things had started flowering in 2010 (one was a variety of witchhazel that has not flowered since having been severely pruned by bunnies). In 2011 there were also 6 plants in flower by the 17th of March (a new aconite). So in this TPP totally agrees with his esteemed associate to the north at the Plant Postings blog. Since at least another week of rather cold weather is still forecast, 2013 flowering schedule will probably fall further behind that of 2010-11. This is the vagaries of weather, not climate. One the whole it was a mild winter. A couple of nighttime lows flirted with 0 F. There appears to be more plant damage because of the lack of snow cover so that growing tips of shoots and leaves have been damaged. My helianthemum looks rather shabby, but should recover, and a newly planted Leptodermis may be toast. Every thing else looks fine. Last spring, the unseasonable early warm weather resulted in no apples and no pears because they then got frosted. Late springs are a bummer because of cabin fever, but it's safer for gardening with less chance of frosty surprises.

St. Patrick's Day botanical question

This could be someone having their fun with a jocular, easy-going academic botanist because it's sort of a bit too much of a coincidence for this to arrive in my email box on March 17th. A "curious student" asks: what happens to an aquatic plant if you put green dye into the water? Well, that is sort of interesting. Plants are green because chlorophyll absorbs wavelengths at the red-yellow and blue-purple ends of the spectrum of wavelengths that compose visible light, so the wavelengths transmitted or reflected will be green. Water dyed with a green pigment will do basically the same thing, so an aquatic plant in green water will get less light to absorb because more of the non-green wavelengths will be absorbed by the water than usual. Chlorophyll became the photosynthetic pigment of choice because if evolved in an aquatic environment where it absorbs those wavelengths that best penetrate water which is a great filter, and just in case you don't get the connection, land plants have an aquatic ancestry. And there's gobs of evidence that support that statement. One demonstration that my students perform is to shine light on a test tube full of some motile algae, usually Chlamydomonas, but the test tube has a black paper sleeve on it with little port holes each covered with a bit of colored cellophane, and one left just open. The algae have eye-spots and can respond to light, so when you remove the sleeve after a bit, there are bands of green caused by the migration of the algae to those port holes where they have accumulated to get the best light. So a red cellophane looks red because it absorbs the other wavelengths while red light passes through, and a pretty good band of green will be found next to the red light port hole, and so on. Now what will happen to an aquatic plant that finds itself in the Chicago River today? Nothing good! Yeah, if you didn't know this before, they dye the river green. Seriously.

This could be someone having their fun with a jocular, easy-going academic botanist because it's sort of a bit too much of a coincidence for this to arrive in my email box on March 17th. A "curious student" asks: what happens to an aquatic plant if you put green dye into the water? Well, that is sort of interesting. Plants are green because chlorophyll absorbs wavelengths at the red-yellow and blue-purple ends of the spectrum of wavelengths that compose visible light, so the wavelengths transmitted or reflected will be green. Water dyed with a green pigment will do basically the same thing, so an aquatic plant in green water will get less light to absorb because more of the non-green wavelengths will be absorbed by the water than usual. Chlorophyll became the photosynthetic pigment of choice because if evolved in an aquatic environment where it absorbs those wavelengths that best penetrate water which is a great filter, and just in case you don't get the connection, land plants have an aquatic ancestry. And there's gobs of evidence that support that statement. One demonstration that my students perform is to shine light on a test tube full of some motile algae, usually Chlamydomonas, but the test tube has a black paper sleeve on it with little port holes each covered with a bit of colored cellophane, and one left just open. The algae have eye-spots and can respond to light, so when you remove the sleeve after a bit, there are bands of green caused by the migration of the algae to those port holes where they have accumulated to get the best light. So a red cellophane looks red because it absorbs the other wavelengths while red light passes through, and a pretty good band of green will be found next to the red light port hole, and so on. Now what will happen to an aquatic plant that finds itself in the Chicago River today? Nothing good! Yeah, if you didn't know this before, they dye the river green. Seriously.

Tapas Saturday Shopping

It's a rather bleak looking Saturday, not a good day for outdoor work, and this is probably a good thing because the indoors need policing prior to having our dinner group arrive. Tonight's menu is Spanish and tapas, which should be fun. Presently we're making a shopping list, and blogging, only one of which is deemed useful by a narrow majority of those present. The hardest thing to find is one of the most central of ingredients: Spanish sherries. Over the past 30 years here in a small university city in the upper midwest many things have become much more common. Cheese used to be a serious problem, but now even groceries have a reasonable selection. Far more diverse selections of beer and wine are now available. You find more exotic fruits and veggies. But for some reason sherries remain uncommon with little diversity. TPP used to get a nice bottle every Christmas because my lovely wife went on a shopping expedition to ChiTown. This year he got an extremely nice bourbon, so that was not a complaint. A successful shopping expedition this morning will require that we find a fairly decent amontillado because obviously sherried chicken livers require sherry. It's also important because obviously the cook needs a little glass to sip while cooking or the recipe won't come out right at all as is well known. Our foraging expeditions generally follow the 90-90 rule where 90% of all the items you want are found at your first stop, and the remaining 10% of the items take you to the other 90% of places to shop. Well, our caffeine titer seems to have reached a functional level, so our shopping is about to begin, which means the blogging must end.

Fly-wheel bicycle

Funny, TPP first read the title of this article as "fly-weight bicycle", which sort of makes sense, but the real topic, fly-wheel bicycle makes great engineering sense too. The principle of a fly-wheel (the black thing in the center of the bicycle frame) to conserve energy, capture the energy from a moving object, and then use that energy to get the vehicle moving again is nothing new. TPP first remembers learning about this from trolleys in places that still have trolleys. And of course, fly wheels are used in hybrid car technology, but applying this principle to bicycles is very creative, which is what you want engineering students to be, because one of the big problems with using pedal-powered vehicles in an urban environment is that the frequent stops rob you of all the energy you used to get your vehicle up to speed. And unless you are one of those stupid bikers who like running through intersections as if the rules of the road don't apply to you (we think of them as incipient "hood ornaments"), stop you must, but the expenditure of energy to get going again is a bummer. However a fly wheel can capture than kinetic energy and allow you to reapply it to getting your bike back up to speed again. Now how can that get engineered into my semi-recombent bicycle?

Funny, TPP first read the title of this article as "fly-weight bicycle", which sort of makes sense, but the real topic, fly-wheel bicycle makes great engineering sense too. The principle of a fly-wheel (the black thing in the center of the bicycle frame) to conserve energy, capture the energy from a moving object, and then use that energy to get the vehicle moving again is nothing new. TPP first remembers learning about this from trolleys in places that still have trolleys. And of course, fly wheels are used in hybrid car technology, but applying this principle to bicycles is very creative, which is what you want engineering students to be, because one of the big problems with using pedal-powered vehicles in an urban environment is that the frequent stops rob you of all the energy you used to get your vehicle up to speed. And unless you are one of those stupid bikers who like running through intersections as if the rules of the road don't apply to you (we think of them as incipient "hood ornaments"), stop you must, but the expenditure of energy to get going again is a bummer. However a fly wheel can capture than kinetic energy and allow you to reapply it to getting your bike back up to speed again. Now how can that get engineered into my semi-recombent bicycle?

Field work looms

Our field research season begins as soon as the first shoots appear. So now a lot of planning has to be done to get all of our ducks in a row so you do the right things in the right order in our usual near futile attempt to wrest some meaningful data from the bosom of Mother Nature. One difficult problem is that some events are so ephemeral that you don't have long to study them. Here's an interesting one. Shoots of the lousewort emerge (soon!) on our prairie with a dark purple color, anthocyanin, but a certain small percentage, roughly about 20 percent, are green with no hint of purple color. By the time the plants reach flowering season in just a few weeks, the weather has warmed and the purple color faded such that the two forms cannot be distinguished. Past measurements also show that on cold sunny days, the purple rosettes are a few degrees warmer than the green rosettes. Does this translate into any resource or reproductive advantage? This is hard to determine, but that's what we're working on. And we're also interested to figure out the genetics of these color morphs. Maybe the green morph is inherited as a recessive gene? So some reciprocal pollinations will be made. Hopefully the prairie will be burned before we start doing our field work, and not while we are doing field work!

Our field research season begins as soon as the first shoots appear. So now a lot of planning has to be done to get all of our ducks in a row so you do the right things in the right order in our usual near futile attempt to wrest some meaningful data from the bosom of Mother Nature. One difficult problem is that some events are so ephemeral that you don't have long to study them. Here's an interesting one. Shoots of the lousewort emerge (soon!) on our prairie with a dark purple color, anthocyanin, but a certain small percentage, roughly about 20 percent, are green with no hint of purple color. By the time the plants reach flowering season in just a few weeks, the weather has warmed and the purple color faded such that the two forms cannot be distinguished. Past measurements also show that on cold sunny days, the purple rosettes are a few degrees warmer than the green rosettes. Does this translate into any resource or reproductive advantage? This is hard to determine, but that's what we're working on. And we're also interested to figure out the genetics of these color morphs. Maybe the green morph is inherited as a recessive gene? So some reciprocal pollinations will be made. Hopefully the prairie will be burned before we start doing our field work, and not while we are doing field work! Sorry if you saw this blog before. Apparently using the less than symbol makes the program think everything after it is some sort of html statement and it goes goofy. What a surprise!

Don't ever do this

Books are big complex things, the more so because smaller presses require the author to basically do everything. Three parts all have to agree with each other: the text, the figures, and the figure captions. For a variety of reasons, but mostly because of resolution, and too little of it, TPP finds himself redoing a lot of figures, but along the way not everthing works out just exactly the same. You find a better image over here. You don't want to pay a publisher to use an image over there, so you have to get a replacement to avoid plagiarism. A colleague helps you out with an image, a terrific image, one that you have to use even though it means modifying a plate, again. And worst, as a result you think of a better way to present things, and this requires you to shuffle a couple of other items to make this work. You make this one little change in all of this and it's like knocking over one domino in a long row or a large network of dominos. Something like 32 individual images or illustrations were arranged into 16 plates, and when you get done you've got something like 31 individual images and illustrations arranged into 13 plates, so now the chapter text and figure captions have to be updated, corrected, jiggered around, the figures renumbered and reorganized to make everything come out even again. It took all day, and TPP is exhausted. Only one more chapter to go, plus all the tough items that were passed over along the way. And the appendices, all the appendices, containing another 62 figures!

Day light savings time & gardening

There seems to be more grousing about daylight savings time than usual, and considering how many time pieces these days automatically reset themselves, it's hard to figure out why, but the general theme is that DST isn't needed anymore. TPP is willing to bet that the writers of such opinions are urbanites, people who live in a totally artificial environment in the first place. An hour one way or the other means little in their artificial lives. However, for us working gardeners, that extra hour of daylight in the evening is just great. If not for working for a living, the daily schedule could be shifted to the actual daylight hours no matter what the clock says, but us 8-to-fivers need light in the evening. TPP shifts his schedule to sun time whenever he's working in the tropics, and one of his plants flowers (groan) at first light (about 5 AM). The people who are carping about DST obviously don't garden, so they don't see any use to having the minor inconvenience twice a year. This is a more general problem because urban areas are centers of population removed from nature so issues like DST and conservation in general are of little interest and yet they have the voting clout that determines issues. Do we need a gardeners lobby to prevent tampering with DST? If DST was done away with what would Hoosiers have to revolt against? Now if only someone could figure out how to re-program the internal cat it's-breakfast-time clock, and as you might guess they like the spring forward (Yea, early breakfast!).

Teaching botany to physicists

Physicists are pretty bright guys, but they really don't have a clue about biology. In the USA science curricula do a weird thing. If you study biology, you generally have both a chemistry requirement, which is sometimes quite substantial, and a physics requirement. Geology is left out of the equation although in many field geology is more relevant than physics. Chemistry curricula have their students take physics, but never biology, and this is rather strange considering the broad interface that exists between the two fields. Physics majors usually take math. This is why biologists in general know more about the physical sciences than they do about biology. In an effort to improve collegiality, biologists are being invited to give an informal lunchtime seminars. It was pretty strange because they asked a ton of questions, mostly that had nothing to do with my research, they just wanted to hear a biological perspective. "Are botanists alarmed/worried about global warming?" Yes. "What do you think about the denialists?" It worked well for big tobacco, so the same people are using the same strategy. It's easier to cast doubt on the science than it is to argue policy. "What about evolution?" What about evolution? It happened, it's happening, we do our best to understand how. "How do you know if plants are related?" Shared characters, some external, some internal, some purely molecular. "If a plant grew on the west coast, but could grow on the east coast, how long would it take for it to get there?" A flight from Portland to New York takes about 4 hours. "If ginkgo was nearly extinct, how come you now see them all over the place?" Seeds from a couple of small surviving populations were collected and the tree became a cultivated species and we've, humans, have moved it everywhere. "So if it can live almost anywhere, why was it nearly extinct, and how come it was once widespread as the fossils show?" Good question, we don't know, but it lives almost anywhere with our human assistance. It hasn't escaped into the wild anywhere. While ginkgos were widespread in the fossil record, it wasn't this species, but a whole lineage of ginkgo related plants. "Why doesn't ginkgo have any diseases?" Hmm, so physicists have an inordinate interest in ginkgos, why? Well, when you almost become extinct, the organisms that depend upon you have a very tough if not impossible time surviving. The population of ginkgos gets to small to support other populations. "Why do you go to the tropics?" Tropical food is great, but generally biologists love the tropics because of the diversity, which means lots of interactions, complexity. In the specific my research is centered around tropical trees in the magnoliid lineage.

It was an interesting exchange, but many of the questions showed their lack of biological understanding. So hopefully this was helpful.

It was an interesting exchange, but many of the questions showed their lack of biological understanding. So hopefully this was helpful.

Bye, bye, bunnies!

Our wildlife friendly yard is so friendly it harbors a remarkable number of fox squirrels and rabbits. Foxes do frequent the yard every so often, and so do Cooper's hawks, but they are primarily bird predators. So while enjoying our lunch, it seemed as if rather few squirrels and birds were around. Then our attention was drawn to activity high above in the crown of a large tulip tree, a mating pair of red-tailed hawks! Nest making activities and mating were ongoing. A couple of pairs of Cooper's hawks live not too far away and they often forage in our yard, but the red-tail is not a common urban hawk although quite common outside of town. So how many rabbits does it take to feed a family of red-tailed hawks? Oh, this is quite exciting, and a new bird record for our property. Bye, bye, bunnies!

PT technology failure

Some technological failures are just so obvious. This particular PT technology of no great reknown was adopted to save money; the old tri-fold paper towels were just too expensive, but you only had to use one and the dispenser was so simple the only way it could fail was to be empty. The new paper towels come in a roll of much lighter weight paper and you need to tug down on the paper to dispense the towel and cut it off of the roll, but this takes a bit of force, and one is just barely adequate. Now here's where the technology actually fails, and in the process demonstrates some industrial research by some dunderheaded paper-perforating engineer, you know the type who design paper cutting, paper perforating equipment for a living, but then who decide it's more fun to fix grand pianos. Hmm, OK, yes, that's a bit too personal and that particular person had nothing whatever to do with this and his piano fixing is a thing of beauty. You see it's quite easy to dispense one of the paper towels, to apply enough force to pull it down, when your hands are DRY! But when your hands are wet, it's almost impossible. This makes you wonder how this PT dispenser was tested? Clearly someone was unclear on the concept. Now what would a good cost analysis discover about the usage, waste, and overall cost of paper towels? Hmm.

Some technological failures are just so obvious. This particular PT technology of no great reknown was adopted to save money; the old tri-fold paper towels were just too expensive, but you only had to use one and the dispenser was so simple the only way it could fail was to be empty. The new paper towels come in a roll of much lighter weight paper and you need to tug down on the paper to dispense the towel and cut it off of the roll, but this takes a bit of force, and one is just barely adequate. Now here's where the technology actually fails, and in the process demonstrates some industrial research by some dunderheaded paper-perforating engineer, you know the type who design paper cutting, paper perforating equipment for a living, but then who decide it's more fun to fix grand pianos. Hmm, OK, yes, that's a bit too personal and that particular person had nothing whatever to do with this and his piano fixing is a thing of beauty. You see it's quite easy to dispense one of the paper towels, to apply enough force to pull it down, when your hands are DRY! But when your hands are wet, it's almost impossible. This makes you wonder how this PT dispenser was tested? Clearly someone was unclear on the concept. Now what would a good cost analysis discover about the usage, waste, and overall cost of paper towels? Hmm.

Friday Fabulous Flower - a screwpine

Although most tropical plants are day neutral, and although most of the plants in our glasshouse are tropical, an great deal of flowering occurs now as the days begin to get longer again. Here's and interesting, and in our glasshouse, unreliable flowerer, a member of the screwpine family (Pandanaceae), Freycinetia multiflora. As can be seen the stem and foliage give this scrambling shrubby vine a bamboo-y sort of appearance, and it can climb by means of adventitious roots to the tropical forest canopy. This one actually isn't in flower yet, but the flowers are tiny and borne on three club-shaped inflorescences hiding (for now) underneath the inner whorl of orange-sherbet colored bracts, which are the attractive part. The smaller image shows one of the inflorescences emerging; these are dioecious plants, and this one bears staminate flowers. According to the literature, pollination is basically vertebrate, nectar/pollen feeding bats and birds, although possums may also effect pollination. On the whole is has a rather unusual look to it, but then again, all screwpines have a strange sort of look to them.

Although most tropical plants are day neutral, and although most of the plants in our glasshouse are tropical, an great deal of flowering occurs now as the days begin to get longer again. Here's and interesting, and in our glasshouse, unreliable flowerer, a member of the screwpine family (Pandanaceae), Freycinetia multiflora. As can be seen the stem and foliage give this scrambling shrubby vine a bamboo-y sort of appearance, and it can climb by means of adventitious roots to the tropical forest canopy. This one actually isn't in flower yet, but the flowers are tiny and borne on three club-shaped inflorescences hiding (for now) underneath the inner whorl of orange-sherbet colored bracts, which are the attractive part. The smaller image shows one of the inflorescences emerging; these are dioecious plants, and this one bears staminate flowers. According to the literature, pollination is basically vertebrate, nectar/pollen feeding bats and birds, although possums may also effect pollination. On the whole is has a rather unusual look to it, but then again, all screwpines have a strange sort of look to them.

Help with plant identification

Arjhay, a reader, needs help identifying a plant, actually just a plant image, a not very good image, so why expect flowers, and it's an exotic ornamental to boot, so it could be from anywhere. Oh, TPP loves a challenge. Arjhay wondered if this was mislabelled as "codiaeum croton"? Yes, it most definitely is not a croton (Codiaeum variegatum). That's a fun genus though what with one each of the 5 vowels (approximately koh-dee-aye-uhm). Back to the plant image. Firstly, notice the opposite leaves and the rather substantial nodes. That helped narrow it down, and truly reject the croton, but it still took a day for the memory to click and send TPP looking in the right direction. First reaction was a purple basil, but it's not minty enough (untoothed leaf margins), and hard to judge scent from an image. Maybe some sort of Acanth, but that didn't seem quite right. Ah, yes, an ornamental Amaranth, and don't ask me how that idea came to me. So my best guess, well-educated, but a guess nonetheless, is Iresine diffusa, the aptly named bloodleaf, but really it's too purple, wine leaf would be better. As you might guess based on the family, the floral display is not the reason people grow this plant, and it has not been common as a house plant for quite awhile now. TPP can't remember the last time he saw this plant. Anyone out there with a better guess? Does this seem right to the hive mind?

Arjhay, a reader, needs help identifying a plant, actually just a plant image, a not very good image, so why expect flowers, and it's an exotic ornamental to boot, so it could be from anywhere. Oh, TPP loves a challenge. Arjhay wondered if this was mislabelled as "codiaeum croton"? Yes, it most definitely is not a croton (Codiaeum variegatum). That's a fun genus though what with one each of the 5 vowels (approximately koh-dee-aye-uhm). Back to the plant image. Firstly, notice the opposite leaves and the rather substantial nodes. That helped narrow it down, and truly reject the croton, but it still took a day for the memory to click and send TPP looking in the right direction. First reaction was a purple basil, but it's not minty enough (untoothed leaf margins), and hard to judge scent from an image. Maybe some sort of Acanth, but that didn't seem quite right. Ah, yes, an ornamental Amaranth, and don't ask me how that idea came to me. So my best guess, well-educated, but a guess nonetheless, is Iresine diffusa, the aptly named bloodleaf, but really it's too purple, wine leaf would be better. As you might guess based on the family, the floral display is not the reason people grow this plant, and it has not been common as a house plant for quite awhile now. TPP can't remember the last time he saw this plant. Anyone out there with a better guess? Does this seem right to the hive mind?

Someone's Irish will be up

Oh, gee! TPP really messed up this time! Some things take time; they can't be done over night or even in a week. Somehow February just disappeared before doing all the things you're supposed to do in that month, and what's really strange about this is that the Phactors did a lot of cooking, but somehow this just escaped my notice. But now St. Patrick's Day is looming and TPP did not corn a brisket! It's terrible when you cannot follow your own advice! This is not a process to be rushed; the results would be disappointing, so it's truly too late. You have no idea how annoying this is because this recipe makes damned good corned beef. The dreams of sandwiches piled high with corned beef and sauerkraut will remain unfulfilled. And of course the ladies in TPP's life are all Irish so perhaps you can imagine their disappointment/wrath (a reaction somewhere on that scale). Even more annoying, having gotten a supply of saltpeter, there wasn't going to be any battle with Homeland Security. Well, maybe the turkey that didn't get eaten for Thanksgiving can be fried (an appeasement) and the corned beef done for Memorial Day!

Uh oh! Missed my anniversary!

No, TPP isn't in trouble because it wasn't THAT anniversary for which there are usually many hints. The Phytophactor blog was started on February 12th in 2008, so it's 5th anniversary just passed. What can be said? The blogging just keeps plugging along at a rate of not quite one a day for a total of almost 1600 blogs. A blog written just 9 days after TPP began blogging remains the most read blog by a factor of about 5, of course it's had lots of time to accumulate page hits. Who knew so many people wondered about whether an artichoke was a fruit or a vegetable? Nature blogs network records the traffic from 2371 nature related blogs, and according to their records, TPP is 157th overall and 8th among plant-related blogs (and it was higher; damned birder blogs!). The total number of page views is hard to figure out because my stats don't go back to the beginning, and there was a period of outage, and different places all record rather different data, but the 500,000 mark is not far away. The good news is that TPP is still having fun, and hopefully y'all are too. But still no entries in the Winter Mix cocktail contest! Let's go people!

Scalia for Pope

The Catholic Church needs a new pope. When scanning the Catholic world

for the right sort of person, the right sort of mentality, one particular name stands

out from all the rest: Antonin Scalia.

There are a lot of reasons this just makes good sense. First, he has the right name. Second,

he has the right look. See how good he looks with red curtains behind him! Three, he likes

robes (just add a bit of red to his current costume

and you’ve got it. Fourth, he likes to

pontificate. Fifth, he’s never

wrong. Sixth, in terms of doctrine, he’s

consistently conservative, a good quality for a pope, except when he isn’t,

which is anytime the citizens of the USA, their laws, the constitution, or the

president disagrees with him (see the fourth and fifth reason above). Seventh, with respect to scripture he’s sure

to be a strict originalist (stonings shall return; the Earth is flat, except

when he isn’t (see previous reason).

Eighth, his appointment as pope would sure solve a lot of problems for

the legal system in the USA and might reverse the decline of The Church in North America (Nah!). Nineth, an

obvious papal name for Scalia exists; can he be named anything other than Pope Justus

of Alexandria (VA) II? Sounds ready made for him. Tenth, this is probably the only job he’d

rather have than the one he has now.

Eleventy, his concerns for minorities and the downtrodden are legendary,

except for helping them vote.

Eleventy-oneth, Scalia already thinks he’s pope. Let’s all give thanks! Let the white smoke rise up the chimney!

The Catholic Church needs a new pope. When scanning the Catholic world

for the right sort of person, the right sort of mentality, one particular name stands

out from all the rest: Antonin Scalia.

There are a lot of reasons this just makes good sense. First, he has the right name. Second,

he has the right look. See how good he looks with red curtains behind him! Three, he likes

robes (just add a bit of red to his current costume

and you’ve got it. Fourth, he likes to

pontificate. Fifth, he’s never

wrong. Sixth, in terms of doctrine, he’s

consistently conservative, a good quality for a pope, except when he isn’t,

which is anytime the citizens of the USA, their laws, the constitution, or the

president disagrees with him (see the fourth and fifth reason above). Seventh, with respect to scripture he’s sure

to be a strict originalist (stonings shall return; the Earth is flat, except

when he isn’t (see previous reason).

Eighth, his appointment as pope would sure solve a lot of problems for

the legal system in the USA and might reverse the decline of The Church in North America (Nah!). Nineth, an

obvious papal name for Scalia exists; can he be named anything other than Pope Justus

of Alexandria (VA) II? Sounds ready made for him. Tenth, this is probably the only job he’d

rather have than the one he has now.

Eleventy, his concerns for minorities and the downtrodden are legendary,

except for helping them vote.

Eleventy-oneth, Scalia already thinks he’s pope. Let’s all give thanks! Let the white smoke rise up the chimney! Very amusing bird & flower field guide

For the biologically challenged there's a fun description of an old fanciful field guide provided by Stoat. All you birders and flower hunters will enjoy this. It's just fun, silly fun particularly if you've ever been confused by clover and plover.

Marriage in Lincolnland Discriminates

Lincolnland is trying to decide if gay marriage will be

legal, and from TPP’s perspective, how can it not be, particularly because

civil unions for gay couples have been approved already? So what’s the controversy? There really isn’t any because the proposed

law does not compel any religion to perform a marriage for any couple they

disapprove of. TPP was quite fortunate to

have gotten married long, long ago, in a place far, far away, because presently the

Catholic Church surely would not allow him to marry one of theirs, if she still

was one of theirs.

Conversely, our church has no problem with the idea of gay marriage, but

our church is prevented from exercising its freedom of religion by another

religion whose practices have become codified into law. Our local dolt representative is a member of

the GnOPe, so he has a non-reasoning, knee-jerk response which seems to simply

be, no, he won’t vote for it. Well, here’s

a message for our representative. In

case you didn’t know, religion does not own marriage here in Lincolnland,

although a religious organization has claimed [Marriage] “is not a civil right;

marriage was created by God and cannot be modified by anybody except God.” Well, folks, you may believe that, but it

isn’t in fact true and that train pulled out of the station a long, long time

ago because any heterosexual couple, even if atheists, can go right down to the courthouse, sign a

piece of paper, and without a single religious blessing or reference, be

married. And so can gay couples except it's a civil union. So the only question

remaining, and this may not have occurred to our representative’s little GnOPe

brain is why aren’t all committed couples equal before the law? Why does the change in wording of civil union to marriage make this a no-no? Is it because of your religious beliefs tell

you it’s wrong if they are gay? If so,

why should your “freedom” of religion be allowed to prevent the freedom of

another religion? Is it because your religion is, nudge, nudge,

wink, wink, the one true religion? So

why do I care what you believe except you get to decide for everyone, a mistake

that will have to be corrected by our democratic process. Perhaps you haven’t read the US constitution

lately; a refresher course is suggested.

Berry Go Round - February 2013

The latest Berry-Go-Round plant blog carnival is up over at Foothills Fancies, and truly, what a round up it is. TPP is flattered by his multiple inclusions, but there is so much more. There are a lot of interesting bloggers posting lots of interesting things about plants. In particular TPP likes the idea of a gymnosperm life list. Why let the birders have all the fun, but just putting together my life list is going to be a chore. If you blog about plants, submit a post for inclusion and let people know where you are.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)